🍁 Analyzing the Impact of the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX) on Crude Markets

In this article, I analyze an oil analyst (Big Orrin’s) discretionary take on ‘the most overhyped (upcoming) flop in the oil market’: the Trans Mountain Pipeline 🍁, using his Twitter discourse and a freight analyst (Ed Finley Richardson’s) articles/tweets. The aim is to go through their views and try and figure out what is going on to learn. Thread link 🧵 and Article link 📰.

Canada is the 3rd largest crude exporter in the world. It exports the bulk of its heavy sour oil sands crude to the US via pipeline networks (~90%), with the remaining going via rail and tanker. However, the rate of production has overtaken demand since 2018. The US receives majority of Canadian crude, the bulk of which go to US midwest (PADD II) and US gulf coast (PADD III).

“Canadians think this will have the effect of increasing demand for Canadian crude oil, putting up the differential and make Canadian producers more profitable”.

The aim is for TMX to be a gateway for Canadian oil to international markets (in particular Asia), pushing up demand and hence the differential, bringing in more dollars for Canada’s economy.

- Problem 1: Lack of Suitable Refineries to Process WCS

- Problem 2: Lack of Suitable Markets

- Problem 3: Freight Cost

- Current Lifts: Sinochem deal

- Impact on Freight Markets

- Conclusion

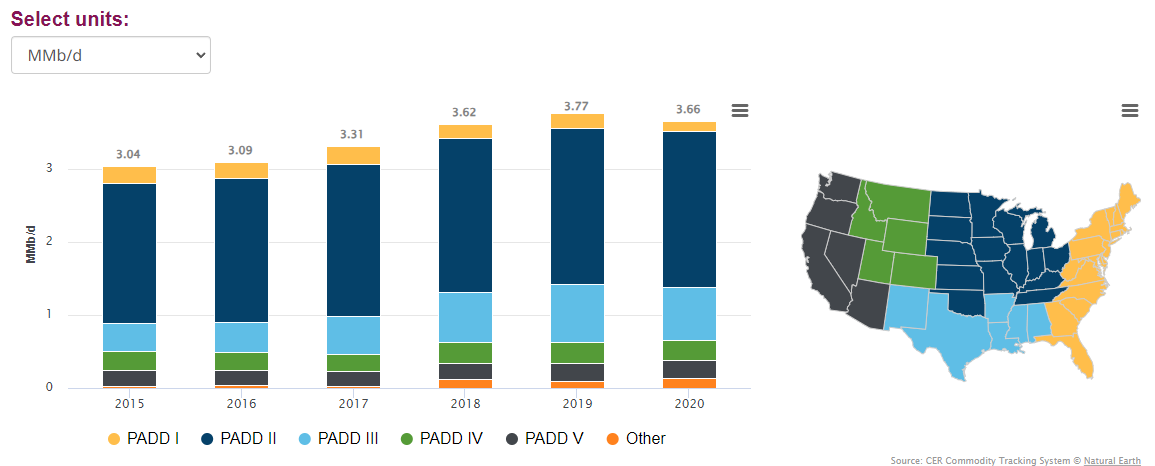

Referencing this barchart, we see in 2020 Canada’s export rate was 3.66 MMb/d. Majority of Canadian crude exports go to the US. Of which, most goes to PADD II (Midwest) by a large margin then PADD III (Gulf Coast). A minority goes to PADD IV (Rocky Mountain), PADD V (West Coast) and a tiny bit goes to Other.

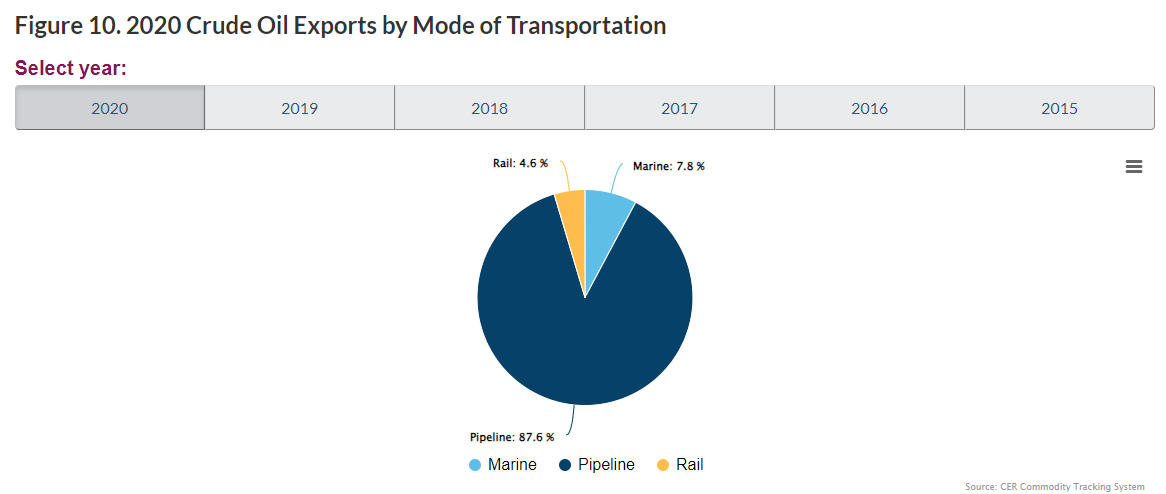

Of the exports, these are a majority is done via pipelines to the US. A small fraction goes by rail, and the remaining via tankers, for waterborne crude off the US West and East coasts respectively.

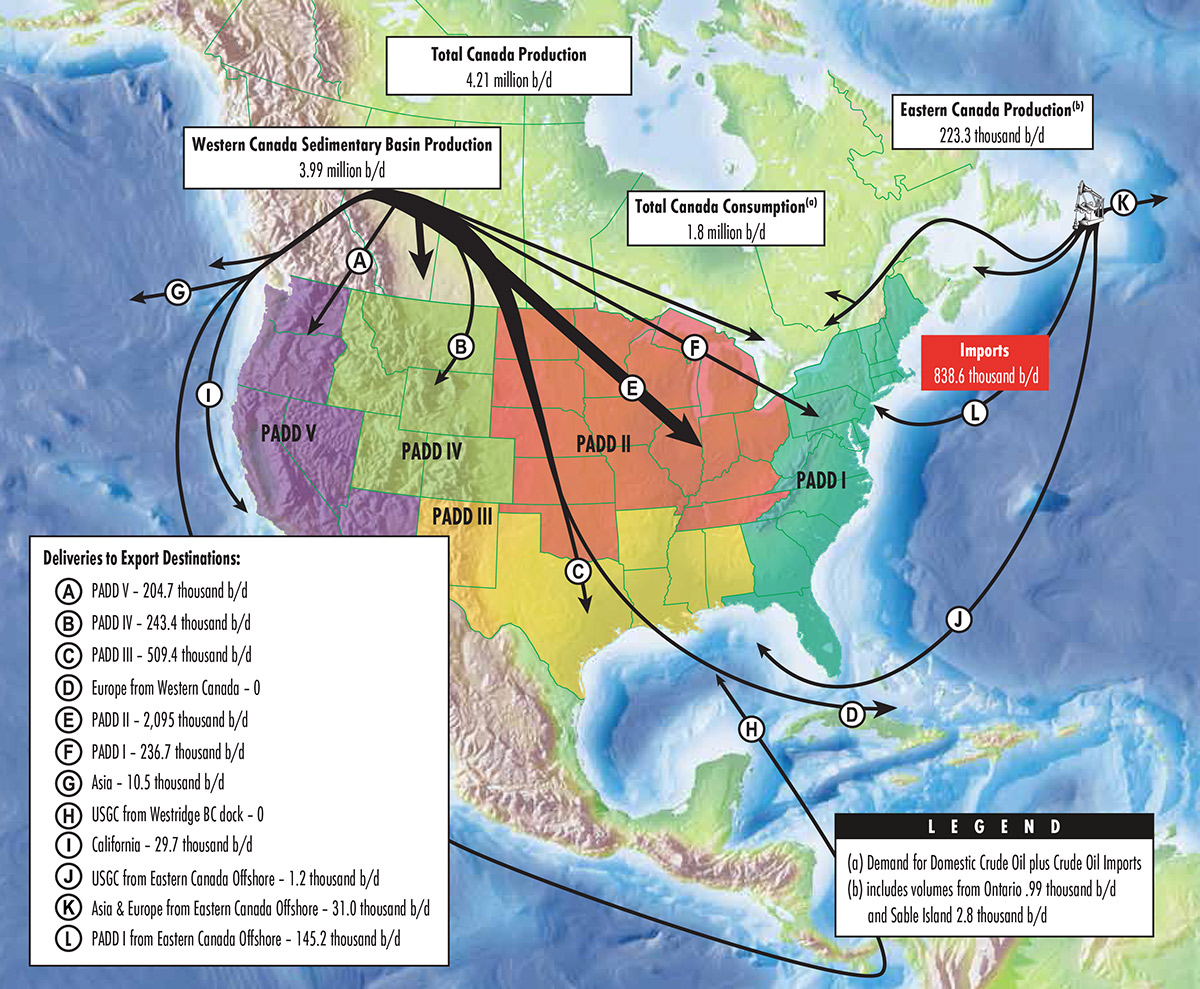

Thus, we have a good geographical intuition of the crude flows to the different parts of the US:

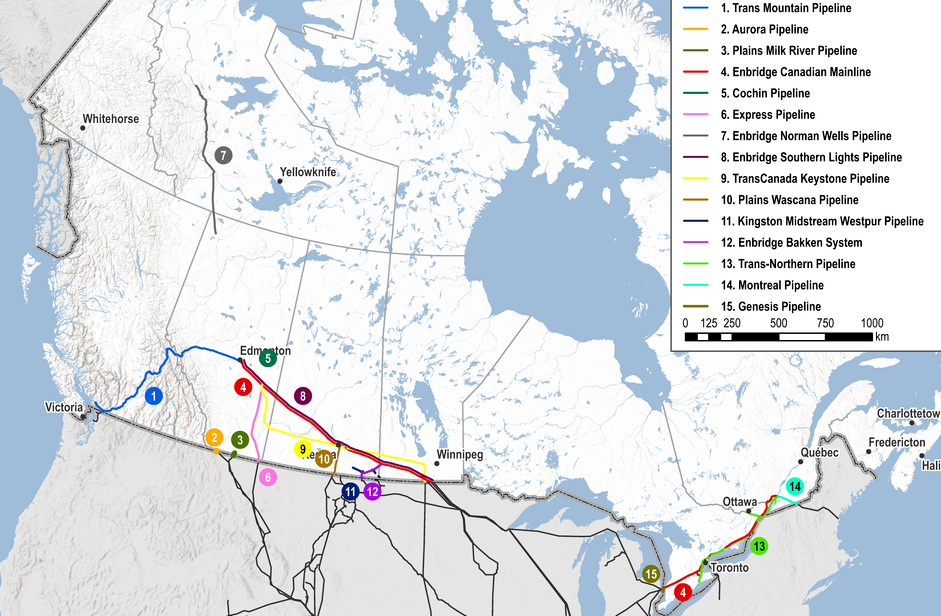

The Canadian pipeline network is built to facilitate this. We can see that the hub of pipeline flows starts from Edmonton and goes outwards. From Edmonton, some crude flows West via the Trans Mountain Pipeline. Some crude flows East and South along the Enbridge mainline and Keystone pipeline.

Enbridge delivers crude and product East from Edmonton to USMW (largest consumer), Keystone goes from Hardisty to USGC (second largest consumer), both Eastward. Trans Mountain goes to West to Vancouver/Burnaby, from there, to USWC.

The majority of flow comes from the Enbridge Canadian mainline (2.9 MMb/d), the Keystone Pipeline (0.6 MMb/d), the Express pipeline (0.3 MMb/d) and the Transmountain pipeline (0.3 MMb/d).

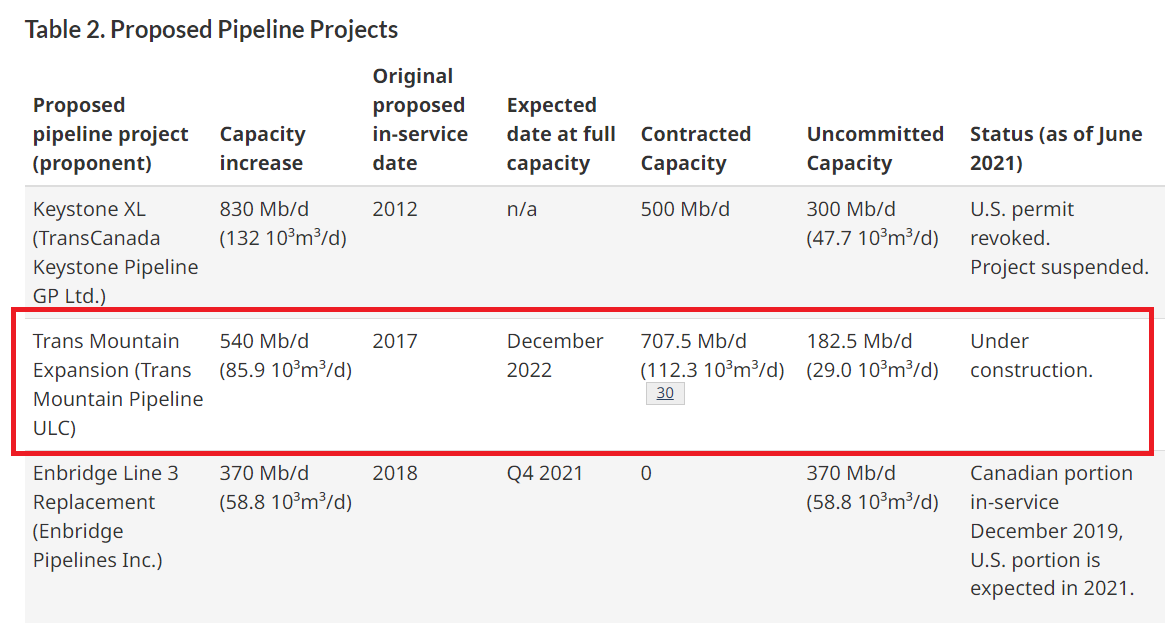

The original Trans Mountain pipeline was built in 1951. In 2013, Kinder Morgan decided to expand it. In 2018, the government bought the pipeline from Kinder Morgan. Today, expansion is complete. The total capacity will increase from 330 kbld to 890 kbld, or tripled the amount and the expanded pipeline will run just beside the original:

80 per cent (708 kbpd) of the pipeline system’s capacity is locked into 15- and 20-year committed contracts. Committed means that shippers pay for capacity regardless if they use it. One could argue that from a shippers point of view, the fact they paid induces a psychological bias or sunk cost fallacy to use it.

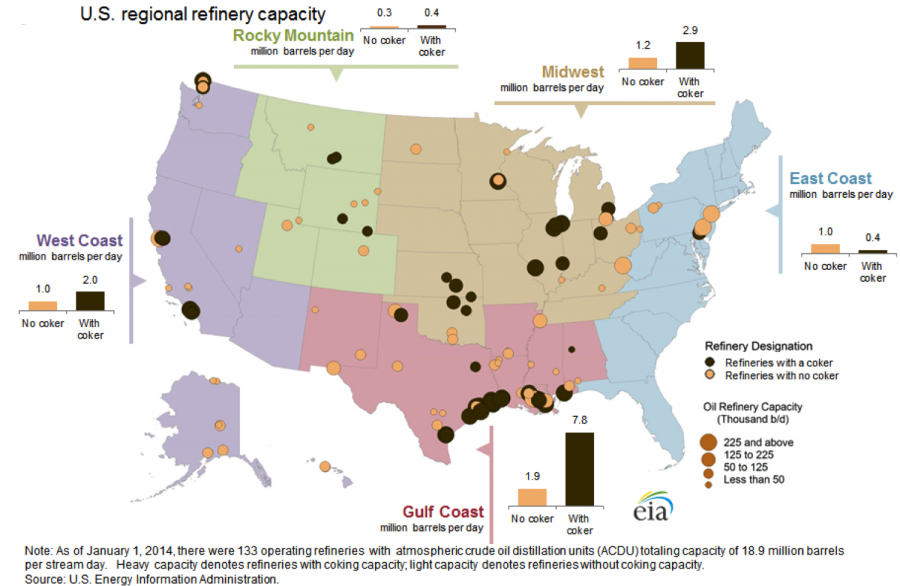

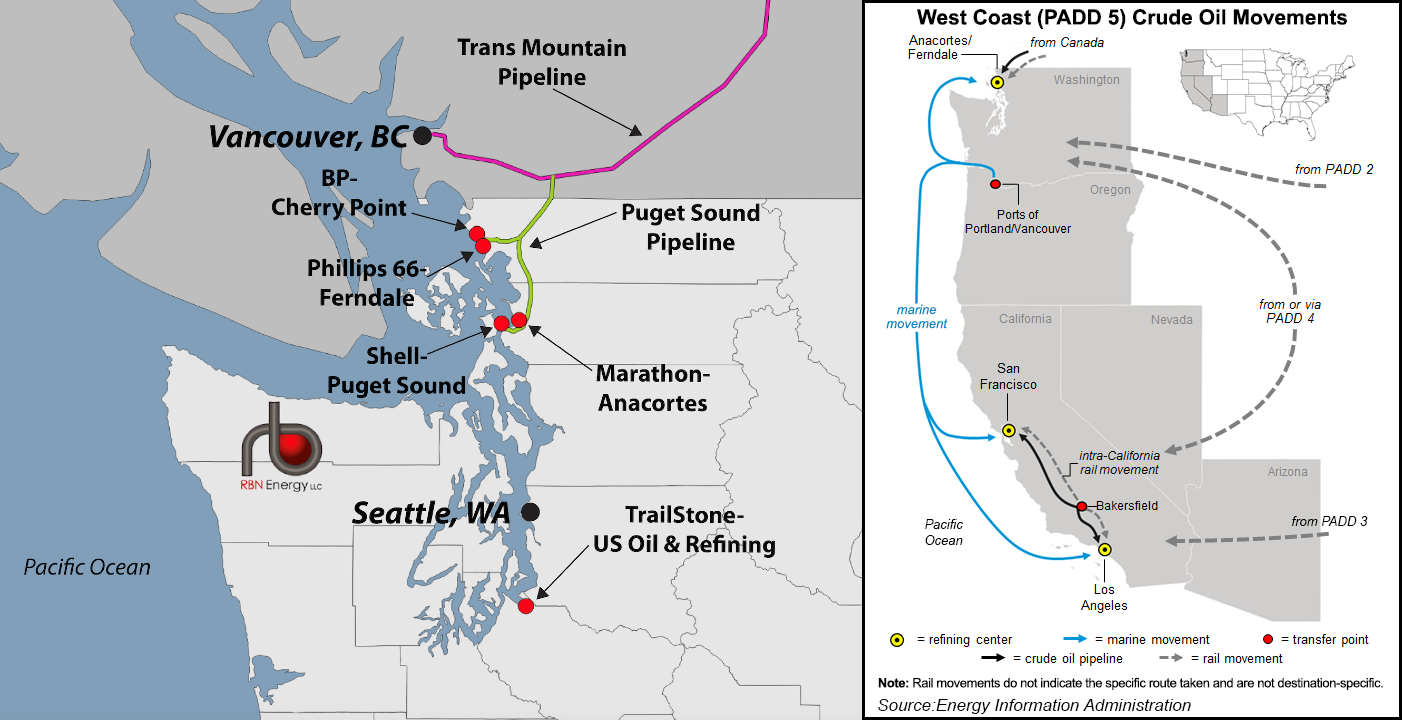

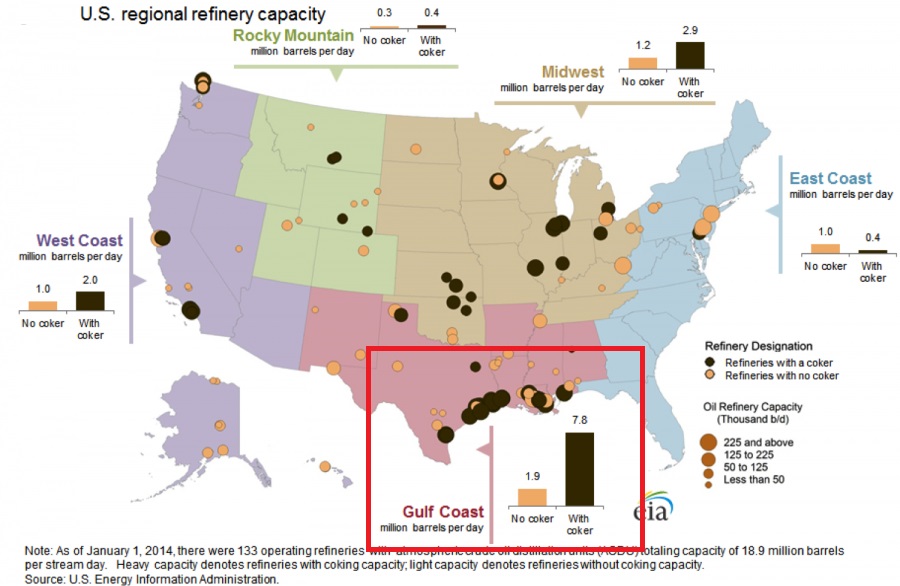

Let’s get a better handle of flows once the crude carried by TMX reaches Burnaby. The most logical option is USWC. A map of US refineries tells us in USWC, there are 3 refining hubs.

One hub is Seattle, Washington, where the US pipeline infrastructure connects to TMX directly. Since it does not extend through Oregon, crude must be transported by tanker along the coast to the remaining two refining centeres in San Franciso and Los Angeles.

So that’s the existing state of affairs, pre-expansion. It would be nice to understand the crude flows for each refinery in the West Coast, their capacity and specs, but that data is not available for non-institutions. But why is the TMX pipeline expansion good in theory?

First off, the demand for crude is inelastic in the short term. Thus, in a simplified manner, an increase in price will lead to a net increase in revenue (the gain from the increase in price is larger than the loss from increase in quantity sold). So, the objective for Canada is to up the price of its crude.

Second, the supply of crude comes from production, while the demand of crude comes from refineries. However, as Canada exports, effective demand is constrained by pipeline capacity. US refineries demand a certain quantity, but the rate of their consumption is capped by the rate of transport of crude through pipelines. Hence, it is the limiting factor.

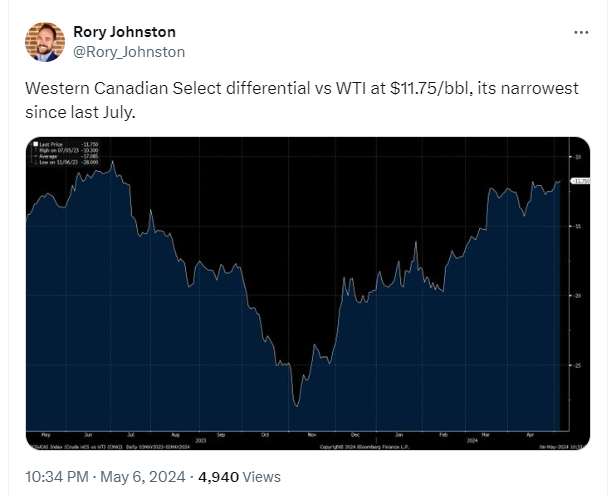

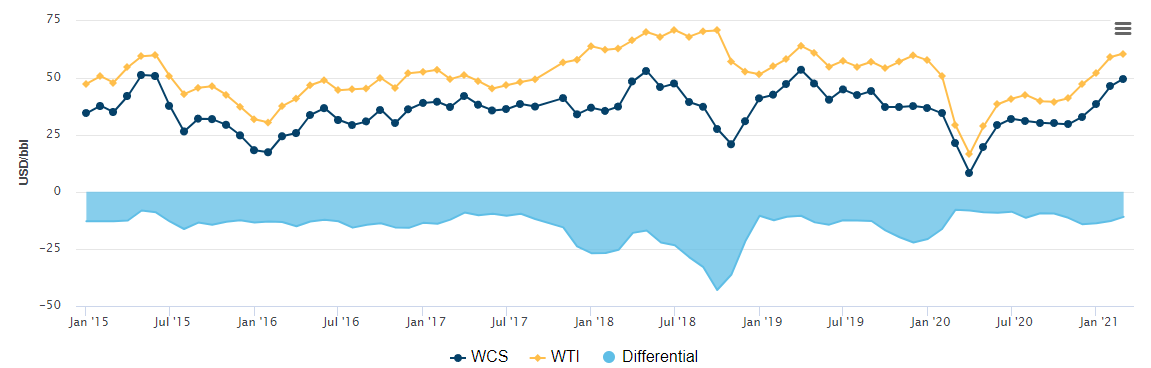

The grade, Western Canadian Select, is priced as a differential to WTI, at a discount because WTI is light sweet and WCS is a heavy, sour and acidic crude. We can see it has hovered historically around the 10-14 range:

The CER (Canadian Energy Regulation) writes, in October 2018, production exceeded pipeline capacity, causing a sharp drop of the differential to -50. Hence, according to them, capacity will affect prices, since pipeline is the main method that crude gets exported out of Canada.

Hence, in theory, expand pipeline capacity → increase effective international demand for WCS → increase crude price (improve diffs) → exploit price inelasticity → profit 💵.

Having a rough idea of flows, we can move on to the actual Big Orrin thread. He argues that this project will have the opposite effect and decrease diffs instead of improving it. Thread link 🧵.

Problem 1: Lack of Suitable Refineries to Process WCS

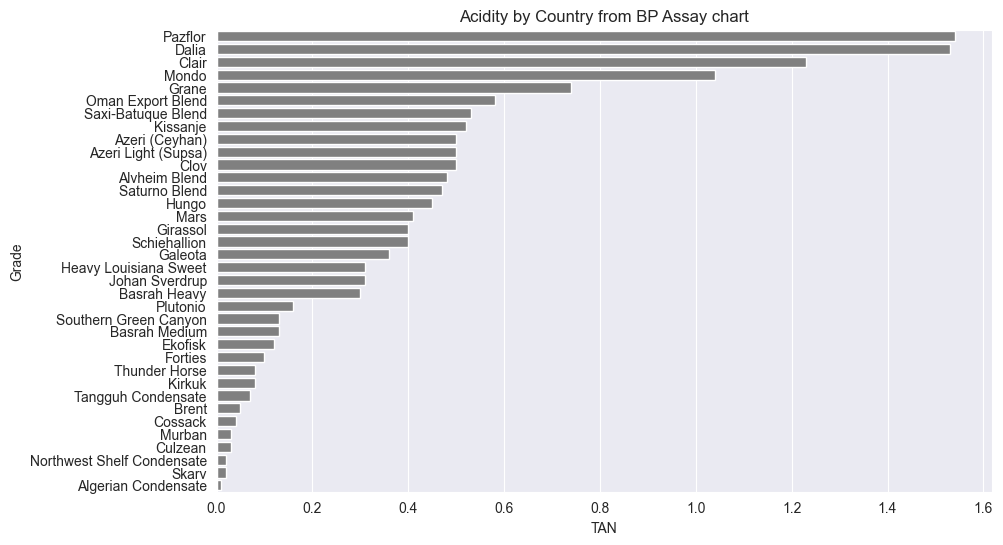

Main one is it might create too much supply for demand. Here are the problems. The crude is very heavy has huge amounts of sulphur but worst of all most will have aTaN of between 1.6 and 2.2. Few refineries can refine that. The problem with acidity is where it comes out in the refinery. That acidity number will increase as the crude is seperated. Because this is very heavy crude, the light crude it is blended with will not help disperse the acidity.

Refineries that are designed for running this crude are mainly based in U.S. Gulf Coast to process similarly acidic Maya. (Little Maya is exported to countries outside of USGC.) Acidity will be the biggest discounting factor in price because so few other refineries can run it.

Canadian crudes is very acidic, with a high aTaN number of 1.6 to 2.2. The Platts periodic table does not have acidity data. Hence, from the BP assay section on their website, we can scrape their table of TaN numbers. Notice how 1.6 or Pazflor (Angolan) crude is the most acidic and 2.2 is way beyond that.

Acidity comes from the napthenic acid and sulfur within the crude. This is expressed in the mg of potassium hydroxide needed to neutralize 1g of crude. An acidic crude has a tan of >0.5, a very high tan crude has a tan of >1. From Big Orrin’s tweet, the main refineries that are capable of this in the US are down south in the Gulf Coast.

It stands to reason USGC refineries are tailored to Maya since Mexico is nearest. I’m guessing since the majority of WCS flows to PADD II, then similarly the midwest refineries are well equipped for acidic crudes. To really get data to support this, we would need a map with refinery specs and capacity, not available publicly.

O: A Coker does not mean you can run high tan. The acidity does not necessarily come out in the very bottom of the vacuum tower feed. Having an FCC is a Massive problem with high tan crude. Further not all have the neutralisation or salt removal process up stream of CDU

X:The napthenthic acids in high TAN crudes are destroyed in the coker heater. The problem with high TAN is everything upstream in the crude & vac towers and associated systems must be “metaled up” to 9Cr-1Mo which is 4-5 times more expensive.

O: That is not necessarily the case. Napthenic acids can come out at anywhere within the vacuum tower. They can get to the Coker via the hydrocracker or FCC. That is where problems happen particularly in the FCC destroying the catalyst

At this point, the discussion goes heavily into refinery technicals. The main point seems be arguing that it is the FCC, not the coker, that determines whether you can run high acidity crudes. FCCs are more present in countries with a heavier focus on gasoline production. This means we should expect Europe to have less FCC capability since of the high diesel use, and more of the US, which is abit confusing. But the overall argument is that it is the high acidity that makes it difficult for most refineries to run

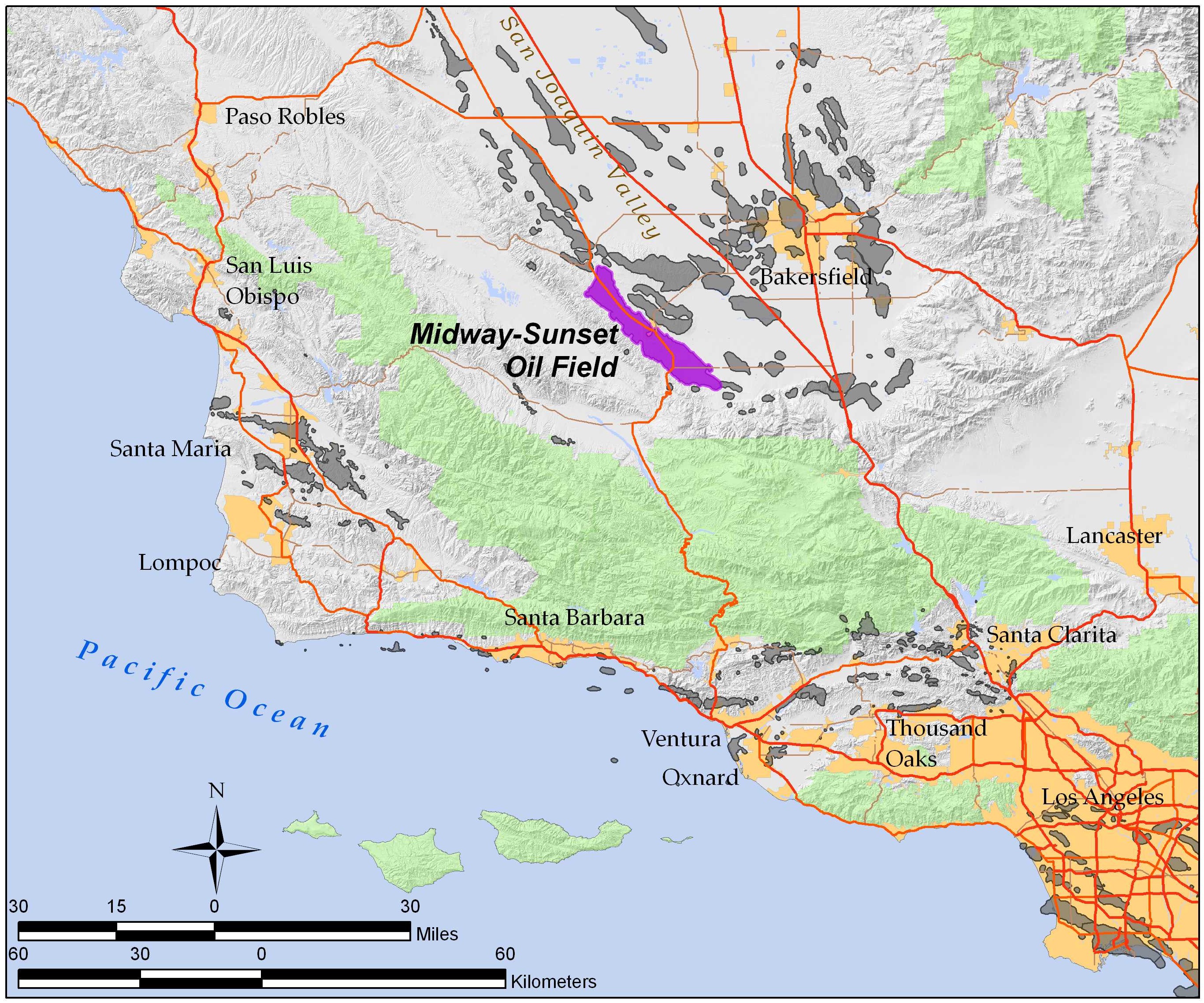

Another potential counter to this is that the USWC might be able to run more WCS:

B: What is the spec of this grade? Socal has several refineries that runs midway sunset oil which is very heavy and sour. O: The quantity produced of midway sunset means it is blended away with other crude oils. It is likely to be a small percentage of the blend used. Would have to be the same with WCS. So demand will be low. Much lower than USGC refiners.

Given this perspective, why can’t WCS be blended too to reduce acidity?

If they try to blend it down into a more manageable crude oil using condensate. It will produce a barbell crude oil. This will send what limited condensate Canada has to silly levels and make the crude uncompetitive against similar crude oils.

The answer is volume, since midway (70kbld) produces a small amount compared to what would come through TMX, so it can be blended with light sweet shale crudes. But the TMX volume is too much to blend. Orrin also states blending with light ends (condensates) is unfeasible due to oil sands not having much anyway.

Thus, the argument is the acidity of the crude limits its demand and hence an oversupply via TMX would not be fully utilized. However, the details dive into refinery technicals, and it’s not possible to find public data to confirm this 😔.

Problem 2: Lack of Suitable Markets

Let’s take a look at the markets for TMX. First China: TMX crude is up against Iranian, Venezuelan even Russian into China. That is the price they will compete against in the long term Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Brazil and many others are on Long term contracts that will not be lost.

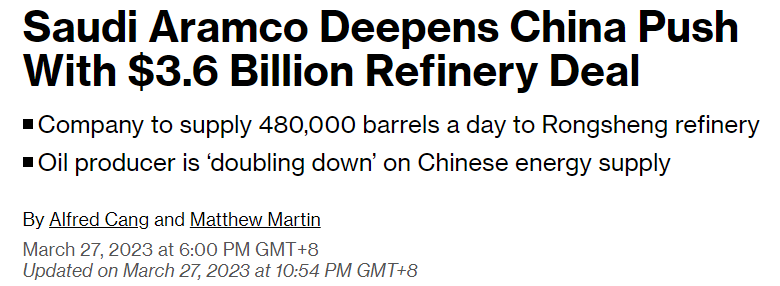

From the previous visualisation post, we can see China imports heavily from ME, Central & SA and Russia, and a good portion of that are long term deals. This makes sense, since Chinese refiners know the country will grow consistently and hence long term deals can meet constant demand. Most recently, Aramco bought a 10% stake of Rongsheng in exchange for supplying it with 480kbld for the next 20 years on long term contract. The same argument goes for India, “which has alot of crude sitting on its doorstep”.

However, a counterpoint is made.

X: Disagree slightly here. From what I’ve heard, Asia and Indian buyers are interested because of OPEC cuts. Reliance needs WCS to fill its cokers and can’t fill them right now. What I am saying is you need to price WCS against Dubai and the economics make sense. O: Real problem is OSPs and, in theory, Saudi will keep to cut further to keep heavy bbls competitive against WCS in Asia. China + India will likely find a way to make it work.

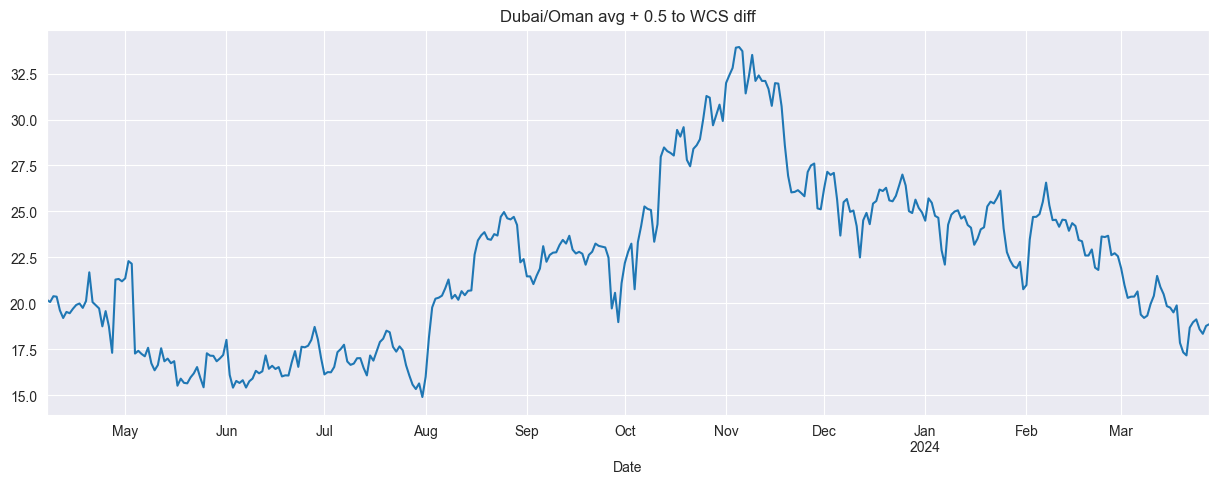

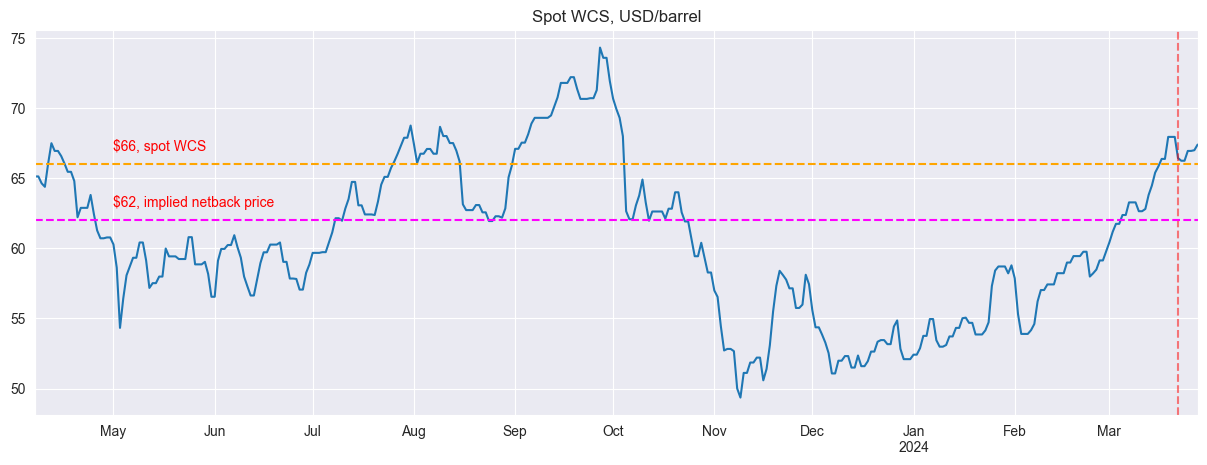

So some investigation reveals the OSP for Arab heavy to Asia was recently raised to 0.50 per barrel in May off the Dubai/Oman average. From this chart (scraped data from oilprice.com) this diff sits at 18.9:

I think this counterpoint implies the cost per barrel difference to ship from Arab Heavy from ME to Asia versus to ship WCS from Edmonton/Hardisty to Asia must be less than 18.9 (or the relevant value in the future) in order for Asian refineries to want to buy cargoes from TMX, and the person making the point is saying it is. But, I don’t have access to any numbers or data to run.

The counter to this counterpoint is that Saudi will reduce/cut OSPs of Arab heavy to ensure their most active customers China and India don’t start getting too much WCS.The next argument concerns US demand. Orrin argues the USWC does not need that much crude empirically:

WC took 3 cargoes in March totalling 1.74mb. TMX has a capacity of 890kbpd which equates to 51 cargoes per month at 550kb per cargo. it equates to 35-40% of WC refinery capacity. That is massive for such a heavy- high tan crude. Likely way too much.

Assuming the March capacity is used as a proxy, 1.74mb per month equates to 60kbd. TMX capacity is 890kbd up from 330kbd. So, West coast refineries took 60/330 or roughly 20% of pre-expansion capacity last month. If we assume the same fraction of capacity, then the expansion would mean 20% of 890 or 178kbd, almost triple the amount of existing flow! So, in this case, unless the West Coast can somehow triple its refining capacity, the additional crude flow from the expansion would not bought by West Coast refineries.

Problem 3: Freight Cost

The last and most expanded upon reason is the freight cost of sending cargoes, delivered by the pipeline to Burnaby’s terminal.

Next problem is the load size. The loadport can only handle Aframax size vessels. To do lightering it must be done at Longbeach in California. 3 Aframaxs are needed and even then that won’t fill a VLCC completely. Freight cost is going to be enormous to go to Asia.

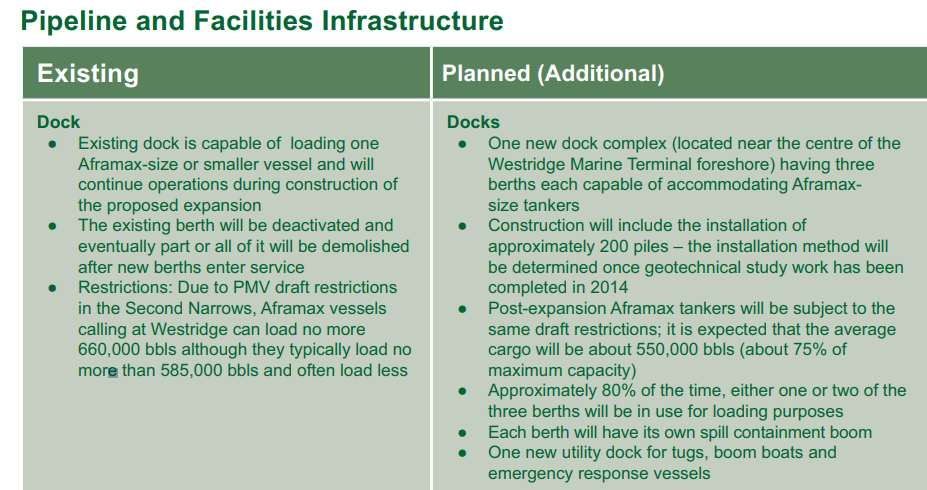

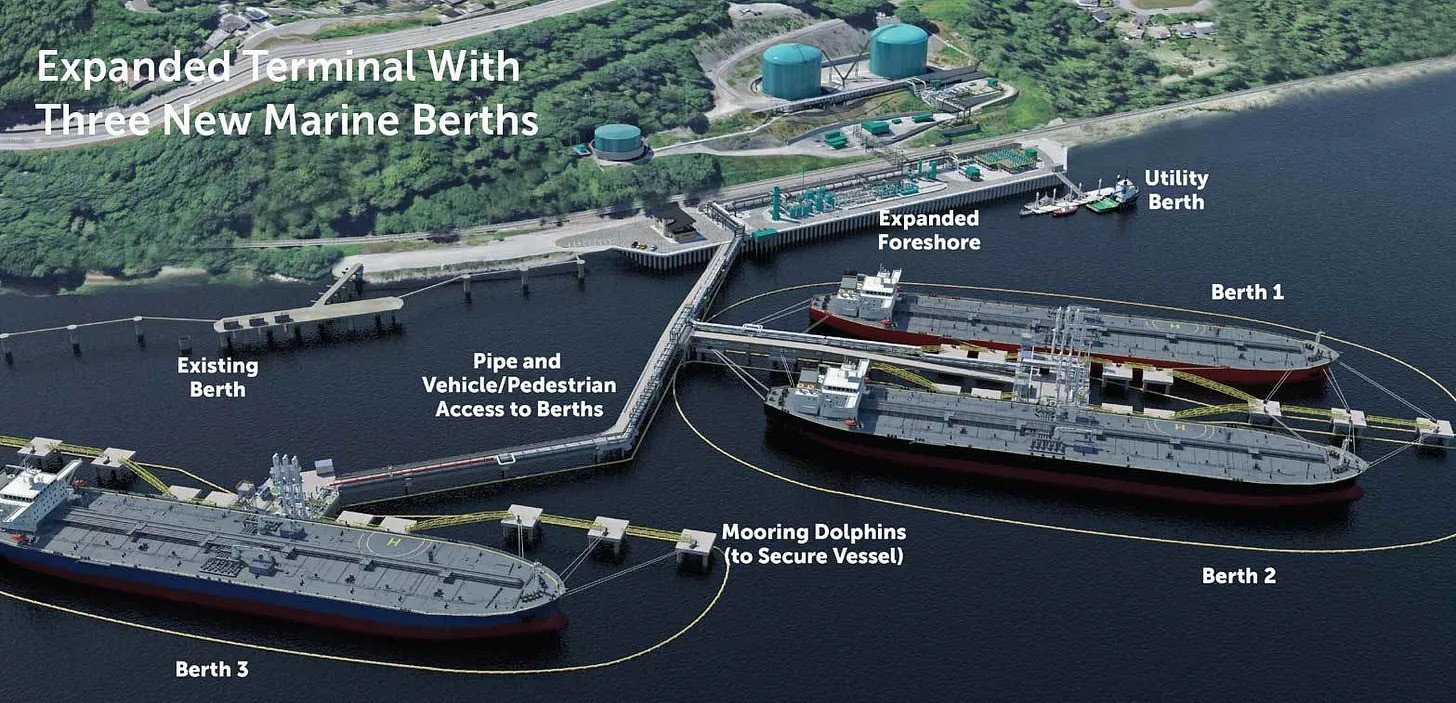

Let’s unpack this tweet. The problem is that the loadport at Westridge Marine Terminal apparently can only accomodate Aframax tankers due to draft restrictions.

Right now, it can only accomodate one Aframax loading due to a single berth but 3 more are planned.

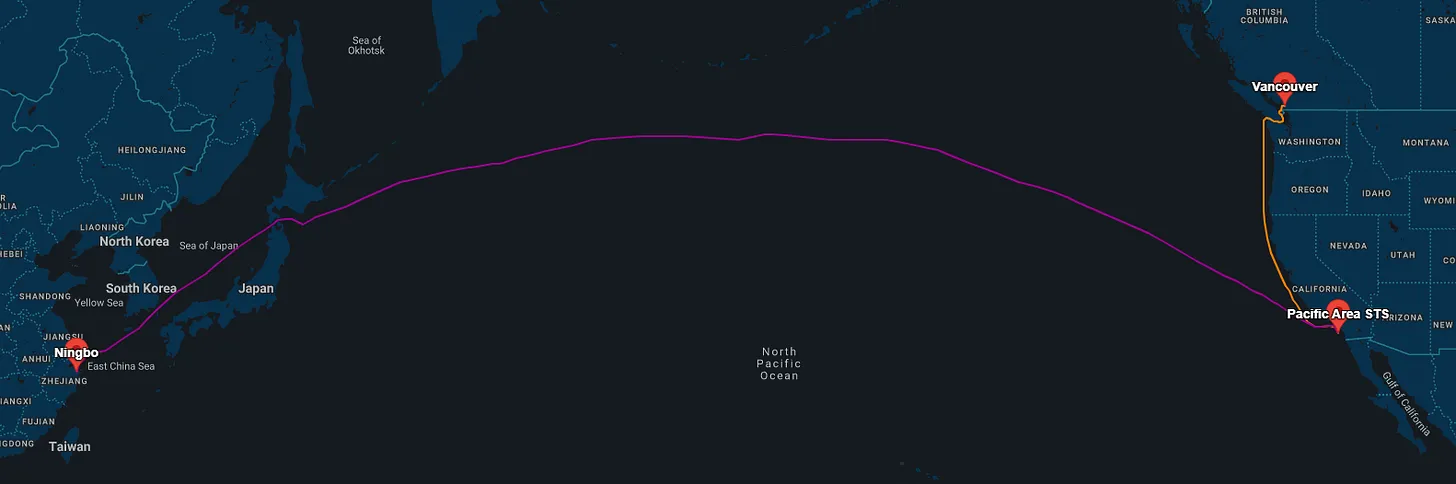

Economically, the larger the tanker, the less the dollar per barrel cost. Thus having an Afra restriction and not being able to load on a VLCC directly already has a cost impact. So economically it makes more sense to lighter or STS (ship-to-ship) transfer to VLCC or Suezmax to lower the dollar per barrel cost, as per the tweet. This would be done by sending Aframaxes to a lightering area: the PAL (Pacific Area Lightering) off California or Panama:

Such a freight route would look like this:

But of course, lightering will impose an additional cost that must be priced into the barrel.

Out of the West Coast prices will have to be very low to cover transit costs, lightering and crude quality. Therefore, that will be the marginal barrel, and that will drag prices overall down for all the Canadian heavy crude.

From Hardisty: TMX toll is more than cost to ship to USGC. Asia: Shipping Afra from TMX with 550kb is always more expensive/bbl than shipping 2mb+ on VLCC from Gulf Only balances if producer sells at a lower price through TMX than to USGC. USGC buyer has new argument to pay less.

So, the argument goes, it is cheaper for an Asian buyer to get the crude to go on Enbridge/Keystone then through US pipelines to USGC, than ship on VLCC across the Atlantic than get it to go through TMX to Vancouver then across the Pacific on an Aframax. Thus, the price of WCS would have to be extra low to tempt Asian buyers. This would be the cheapest or marginal barrel, and hence US refineries would demand that price, thus lowering the differential - having the opposite of the desired effect.

Sadly, there is little public data that I can access to look at the numbers for this argument. But Twitter discourse has some interesting arguments below:

Current Lifts: Sinochem deal

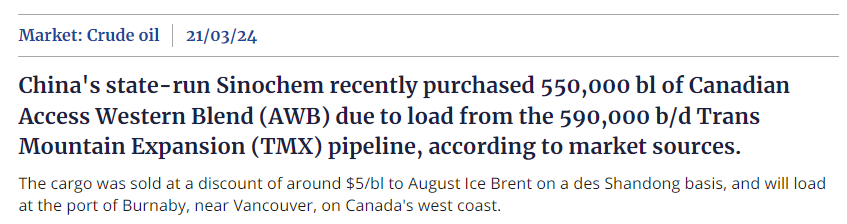

Despite the arguments that freight cost is absurd to lift from TMX to Asia above, the Chinese refinery has agreed to load a cargo of AWB, at a discount of 5 per barrel to August ICE Brent on des Shandong basis, loaded at Burnaby. How does this affect the existing argument? Luckily, there was lots to unpack from Big Orrin:

Cost of delivery is estimated at 10-12 per barrel on an Aframax that pass environmental requirements of loading in Canada. Potentially could be much more expensive if world scale rates strengthen. So ICE Brent -17 at Vancouver.

I couldn’t find much info on the DES term, but assuming it is similar to CIR/CFR, the price Suncor sells to Sinochem includes all costs needed to bring the oil from the production hub to Shandong port, so Suncor must charter the tanker. We can then netback the costs to find out the inferred price of this deal, at Hardisty/Edmonton. Orrin assumes a 12 cost of shipping:

X: I’ve been seeing shipping costs quoted more in the 6ish/bbl range; anything i can look at re: the 10-12/bbl enviro requirement?

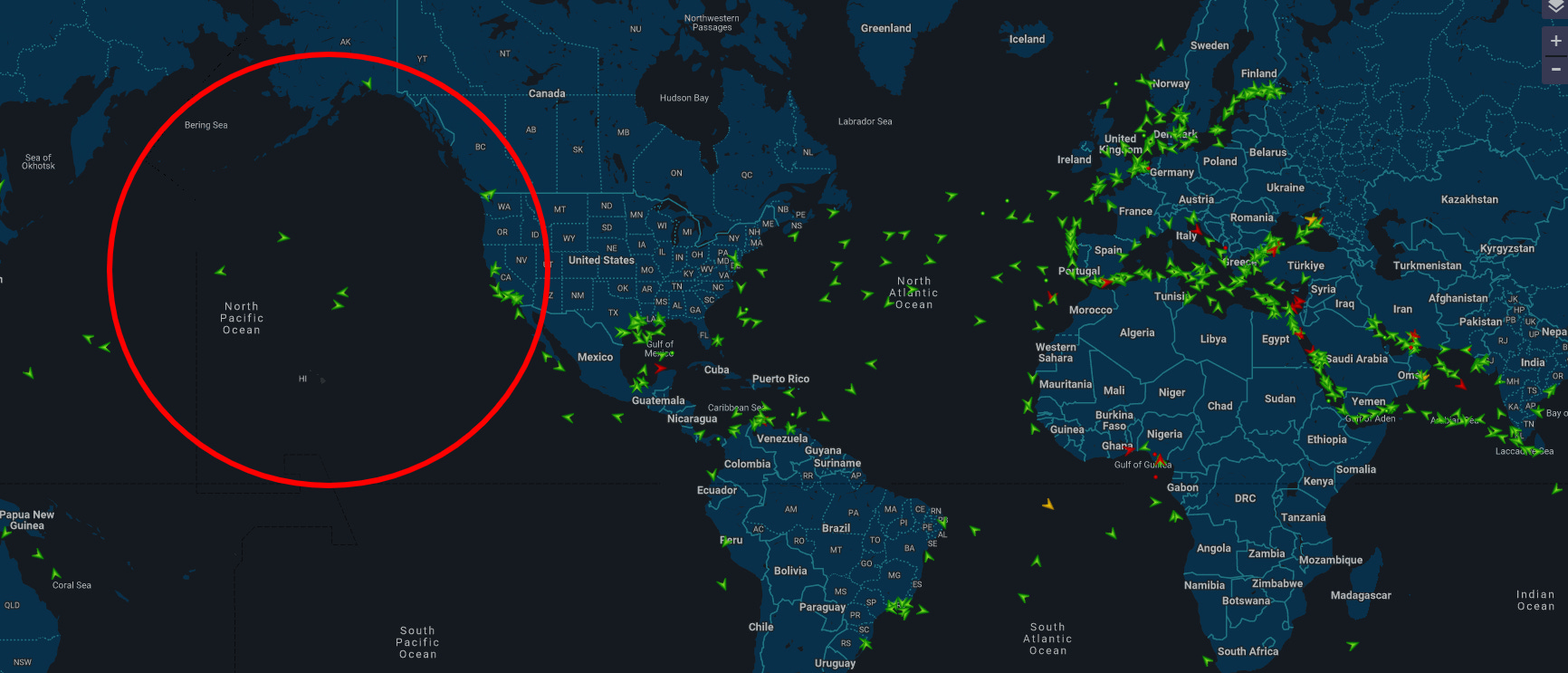

O: The problem is you can only load 550kb which is much less than a full Afra. Afra’s are the most expensive per bbl for vessels. Add that there are few in the northern pacific so it means they would have to relocate without any backhaul options because of the Panama Canal.

O: Round trip at 12 knots is about 47-49 days. There is two day loading window, 38-40 day round trip and then roughly 7 days of wait to discharge. Then you need to consider losses. Thicker the crude the more barrels lost in discharge. Then add security and fuel. Add also that Canada has strong restrictions on the vessel age and emissions so that all makes the new more modern boats that much more expensive.

Costs were assumed to be 6 but Orrin thinks 12. This is per barrel, single Afra from Burnaby to Shandong, across the Pacific, with no lightering. Again, I have no access to any freight rates data, so we can only speculate. Let’s unpack the arguments from the shipowners view.

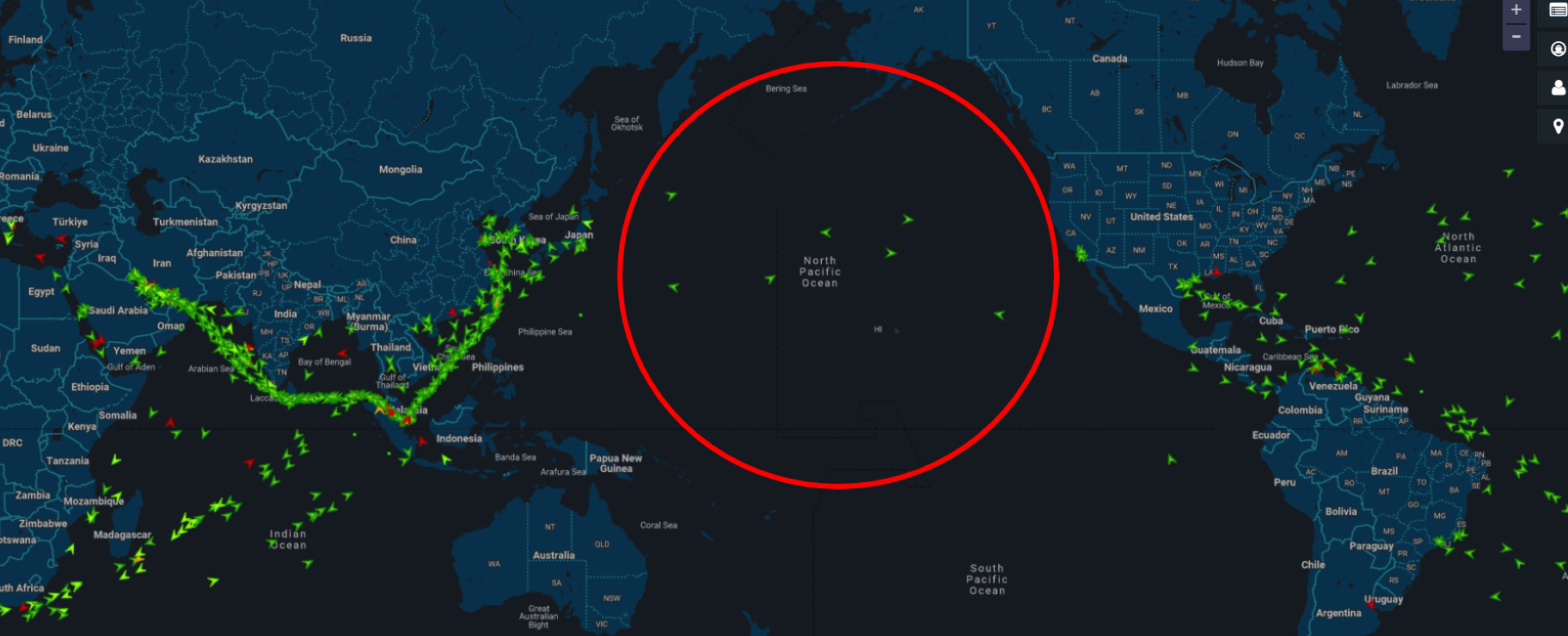

Indeed this article by Ed Finley Richardson shows a map that Afras are pretty sparse in the North Pacific:

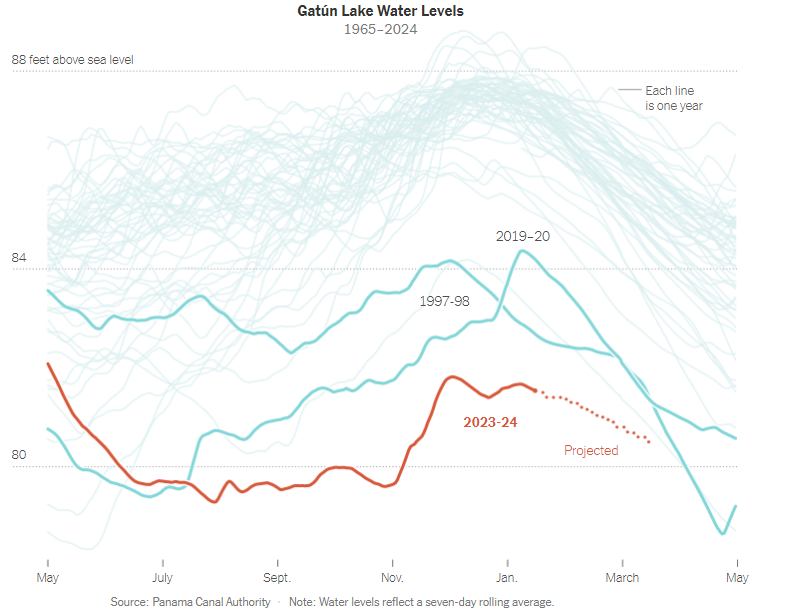

What’s happening with the Panama canal? Apparently, weather. Drought in Panama. The canal operates on a series of locks that draw in water from nearby lakes to raise/lower ships. So, the lack of rain means the rate of ships going through must go down, and that is what the government has ordered. Of course, when rainy season comes, this situation could improve.

A backhaul seems to be a return journey with cargo. I’m not entirely sure on the exact routes, the idea is that Panama canal blockage would limit delivery options on the return journey. This would lead to ballasting (journeying without cargo) and shipowners would demand higher rates to compensate for the opportunity cost, making freight rates more expensive. Returning to the pricing argument:

Consider your 6 freight to be correct. Ice Brent August minus 5 is 79. Take shipping away and you have 73. The Toll on TmX is 62 at Hardisty. WCS is trading at about 66 for same period. Going down TMX rather than Enbridge is losing producers about 4. Problem for TMX is that toll and freight will always be greater than shipping cost to USGC, just because TmX toll is greater than Enbridge cost.

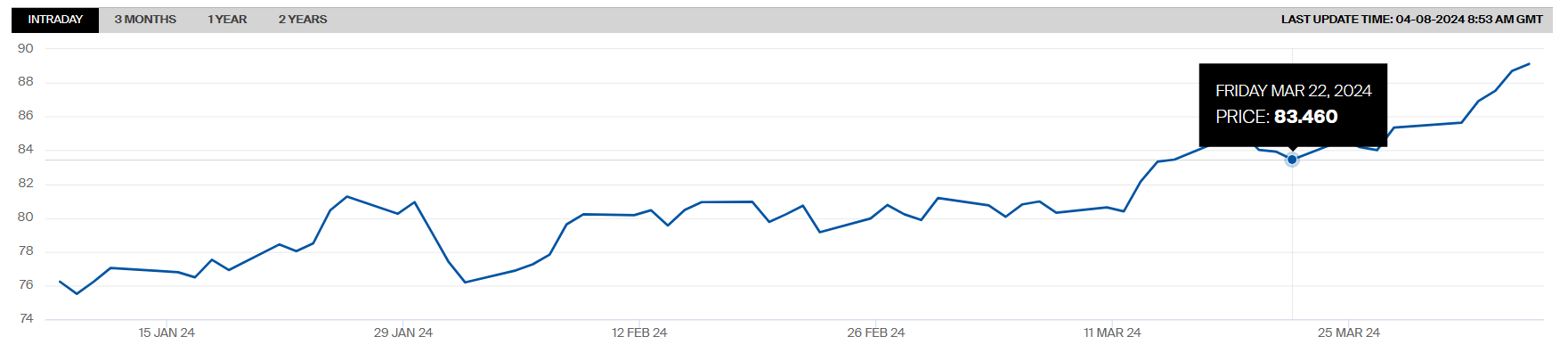

On the tweet date (22 March) the ICE Brent August contract closed at 83.4 :

So to netback you take 84 (ICE Brent August) - 5 (deal discount) - 6 (shipping) - 11 (TMX toll) = 62 or 4 discount to current WCS. And that’s the “true” value of crude sold by Suncor in this deal, which is undervalued relative to the current WCS price of 66. So that’s the marginal barrel argument to bring down the WTI-WCS diff even more. And that’s the Big Orrin argument (or my understanding).

Of course, another tweet says:

X: Can’t free market dynamic fix that? If indeed it’s too expensive, then don’t ship on TMX, till toll come down 4 and then all if good. If only free markets could play out? Are these toll set in stone and shippers already signed contracts at those rates? O: Yes

Earlier on, we noticed that the TMX expansion project had 80% committed capacity. This tweet implies at contracted capacity, tolls are fixed (at 11). So the toll cost is effectively ‘locked in’ and will transmit to the differential.

So from my view, of what I’ve read and done in this article, the logic seems sound. Thus, we should either expect to see the marginal barrel drop as more and hence the WTI-WCS diff as more of the pipeline capacity comes online and deals move Canadian crude to Asian markets at high toll and freight costs, or the pipeline remains unused and nothing happens.

Impact on Freight Markets

Given the black hole of Aframaxes and VLCCs in the Northern Pacific, it’s quite possible that the TMX flow will be bullish for both tanker classes and improve rates, at least in the medium to short term, when refiners wish to ship cargoes out of Burnaby. But sadly, freight is generally not very accessible in terms of articles online, so there’s not much I can say apart from repeating what the articles stance is: that amount of volume of loadings would have significant price impact.

Conclusion

To conclude, there is my first writeup on a discretionary analysis. Do I have any confidence in taking my own view? No. That’s partially because of lack of data. But, what I tried to do was to look at the views of others, then try and put the pieces together, despite the steep challenge of not having any accessible numbers or data that the guys tweeting are using to make their arguments. And I think I learned lots. This is only the beginning.

I chose this thread because it had a diverse mix of topics, from refining mechanics/technicals, to freight routes/markets, to international crude flows.

A collection of threads/discourse from #OOTT that I gathered is available at this Github repo . Moving forward, my aim is to do a few more projects on these market views.